Sargasse on Blue, La couleur de l'onde, 2021

-

1

Sargasse on Blue, La couleur de l'onde, 2021

Algalphabet, from collected seaweed Bifurcaria Bifurcata.

-

1

Algalphabet, from collected seaweed Bifurcaria Bifurcata.

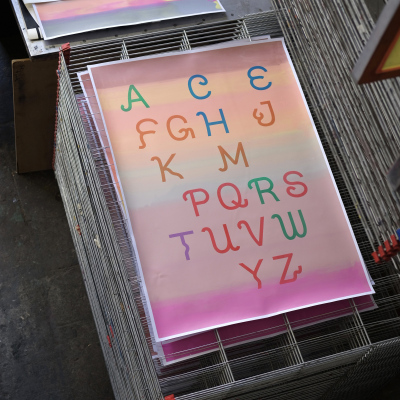

Algalphabet Poster, from the font Algalphabet Bifurcaria designed together with typograph Jonathan Shi.

-

1

Algalphabet Poster, from the font Algalphabet Bifurcaria designed together with typograph Jonathan Shi.

La couleur de l'onde, white quadriptyque 2020.

4 Inkjet photographies in frame, 40 x 40 cm. Edition of 3 + 1 A.P.

-

1

La couleur de l'onde, white quadriptyque 2020.

4 Inkjet photographies in frame, 40 x 40 cm. Edition of 3 + 1 A.P.

Algae Paper Lamp, 2018.

Metal, Wood & Aluminium.

Limited edition 3 ex.

70 x 62 x 30 cm

-

1

Algae Paper Lamp, 2018.

Metal, Wood & Aluminium.

Limited edition 3 ex.

70 x 62 x 30 cm

Bifurcaria Bifurcata

-

1

Bifurcaria Bifurcata

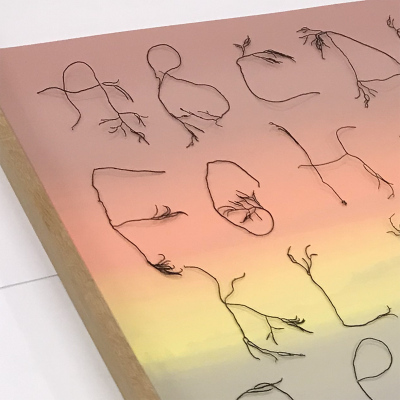

Algalphabet Bifurcaria typeface, 2021. Inspired by the Bifurcaria Bifurcata from the north shores of Brittany.

-

1

Algalphabet Bifurcaria typeface, 2021. Inspired by the Bifurcaria Bifurcata from the north shores of Brittany.

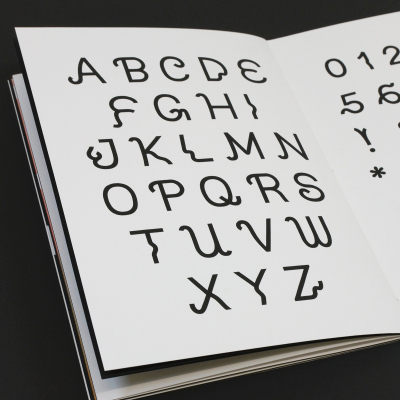

Algalphabet Booklet, 2021. A silk-screen artist book in 99 ex. presenting the genesis of the Algalphabet typeface. 32 x 23 cm.

-

1

Algalphabet Booklet, 2021. A silk-screen artist book in 99 ex. presenting the genesis of the Algalphabet typeface. 32 x 23 cm.

Algae Paper sheets made of green seaweed (Ulva Armoricana).

-

1

Algae Paper sheets made of green seaweed (Ulva Armoricana).

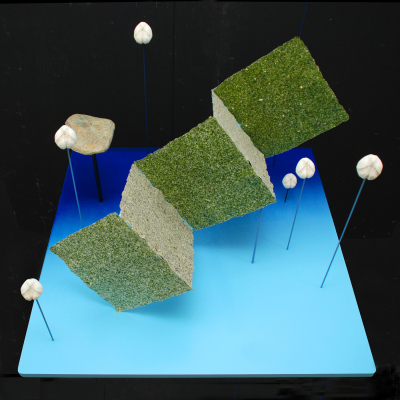

Typologies: Algae Paper sheets, silk-screen printed on MDF, metal rods, dried urchin shells & schist stone, 1 x 1 m.

-

1

Typologies: Algae Paper sheets, silk-screen printed on MDF, metal rods, dried urchin shells & schist stone, 1 x 1 m.

Algae Paper in frame (black exemplar), 43 x 44,4 cm.

-

1

Algae Paper in frame (black exemplar), 43 x 44,4 cm.

Algae Lamp (prototype model #1), 70 x 15 x 20 cm.

-

1

Algae Lamp (prototype model #1), 70 x 15 x 20 cm.

Algae Lamp (prototype model #2), 70 x 50 cm.

-

1

Algae Lamp (prototype model #2), 70 x 50 cm.

Algae Paper diptyque, 220 x 140 cm.

-

1

Algae Paper diptyque, 220 x 140 cm.

Algae Mask (Blowing Kid), 20 x 20 cm.

-

1

Algae Mask (Blowing Kid), 20 x 20 cm.

Algae Masks (various models) 25 x 25 cm each.

-

1

Algae Masks (various models) 25 x 25 cm each.

Algae Paper branches on silk-screened posters, 210 x 200 cm.

-

1

Algae Paper branches on silk-screened posters, 210 x 200 cm.